| ALL |

|

UNITED STATES

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Twentieth-century architecture in the United States exhibits multiple overlapping themes that include historicism, regionalism, and various forms of modernism. Although architects, historians, and critics throughout the 20th century sought continuities,disjuncture appeared more frequently. One attempt at constancy involved reliance on history as the source for design, as in McKim, Mead and White’s Pennsylvania Station (1902–10), New York City, and Robert A.M.Stern’s Darden Business School (1992–96) at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. An alternative approach lay with the regionalists or nativists, who sought a unique American expression based on the local vernacular and, often, landscape, such as with Frank Lloyd Wright’s early Prairie style houses and Antoine Predock’s abstraction of native American forms. The third theme, a quest for a modern architecture, occupied many individuals and includes buildings as diverse as R.M.Schindler’s King Road House (Los Angeles, 1921–22), Marcel Breuer’s St. John’s Abbey (Collegeville, Minnesota, 1953–61), and I.M.Pei’s Louvre Pyramid (Paris, 1983–93). All three examples paid homage to abstraction and advanced building materials and techniques. Ideas concerning the American city have ricocheted from grand plazas, as with John Bakewell and Arthur Brown’s San Francisco Civic Center and City Hall (1912–16, renovations 1995–99); to setback skyscrapers and elevated roads, pictured by Hugh Ferris’s Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929); to monolithic towers with little connection to the city, exemplified by John Portman’s Renaissance Center (1971–77, Detroit); and finally the ideas of Duany and Plater-Zyberk (Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk) for new towns that captured the critical discourse of the 1990s and that make up a movement termed New Urbanism. Instead of singularity, American architecture offers a competition of themes and a bewildering variety of expressions.

American Characteristics

Conditioning American architecture is the unprecedented wealth and standard of living of the country and its emergence as a dominant world power in the 20th century. What would be the nature of American culture and how it would define itself has been a perennial problem as the cult of individuality reigns.

Historicism

The strongest and most continuous theme in American architecture remains an infatuation with history and the employment of imagery from the past. The method of how this past has been quoted—from fidelity to distortion—and the range of appropriation from Colonial to European and Oriental has varied. The semiotician Umberto Eco observed that the American imagination craves the real thing, and to establish that reassurance, Americans fabricate, or reproduce imitations. Architects create buildings in which the quotation is proudly displayed: the English Georgian country houses of David Adler, such as Castle Hill, Ipswich, Massachusetts, (1924–27) or the Roman villa as the basis for the J.Paul Getty Museum (1972–74), Malibu, California, by Langdon, Wilson and Garrett, with Norman Neuerberg as consultant.

The American Renaissance, dominant from, 1890s to the 1930s and led by the firm of McKim, Mead and White and others, posited that American architecture and art could not be invented but, rather, that it should draw upon the classical past of Europe and America. Out of this approach came the great courts of honor at the various American fairs from Buffalo (1901) to Philadelphia (1926). These courts of honor provided a model of civic architecture and led directly to the City Beautiful Movement and civic centers such as Arthur Brown’s in San Francisco and state capitols that lasted well into the Depression, as for example with Cass Gilbert’s West Virginia Capitol (Charleston, 1930– 32) and John Russell Pope’s National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., 1936–41).

Opposed to this classicism stood the medieval revival led by Ralph Adams Cram, who argued for the validity of the Gothic and designed over a hundred churches and significant portions of university campuses between 1900 and 1940. Cram succeeded in creating a Boston-based Gothic School that affected thousands of churches across the country, such as Frohman, Robb and Little’s (and others) National Cathedral (1906–90) in Washington, D.C.

Colonial Revival, whether Spanish, English, or other nationalities, has proved to be the most lasting historicist approach. The myth of Colonial as the truest, and the earliest, American style had an effect on others that appear to be far removed. The restoration of Colonial Williamsburg (1927–) gave great impetus to Colonial Revival and made the brick Virginia Tidewater Georgian house a national image. In Florida and the Southwest, a Mission and then a Spanish Colonial Revival developed as a localized colonial revival response. Since 1926 towns such as Santa Barbara have continued to rebuild themselves along the lines of a Spanish town, even though that history is mostly fictional.

Recognition of the validity of a historicist approach vacillated in 20th-century America. From 1900 to the 1930s, historicism was the accepted norm, and architectural periodicals showed and promoted historical prototypes. However, beginning in the 1920s, the historical approach came under fire, and by the 1940s the appearance in professional architectural periodicals of buildings in historical dress was rare. From the 1940s through the mid-1970s, serious discussion of historicism as a contemporary approach to design disappeared from the profession, the schools, and writings by most critics and historians. Not all historically based design disappeared, for it thrived with builders and contractors at the suburban house level and also in the hands of many local architects. Allan Greenburg’s design for the Brant House (Greenwich, Connecticut, 1979–83), which takes elements of Washington’s Mount Vernon, received rave reviews in the professional press, indicating the changed climate. The work of Hartman-Cox Architects (George Hartman and Warren Cox), who began as modernists but turned to preexisting models, received similar praise. Their Georgetown University Law Center Library (Washington, D.C., 1984–89) and their additions to the Chrysler Museum (1982–89) in Norfolk, Virginia, appear as if they have stood since the 1930s.

The recognition of historicism as a valid architectural approach began in the late 1960s with a reevaluation by architects who became known as Postmodernists and by a group of younger historians who began to investigate the hitherto forbidden (i.e., outmoded) Victorian and Beaux-Arts eras. However, the greatest contributing element to the new historicism was the Historic Preservation movement, which gained great support in the 1960s and 1970s because of new federal and local legislation. From 1900 to the 1950s, preservation had a reputation as elitist—only concerned with the homes of the wealthy and in recreating historical villages. In the 1960s, however, preservationists questioned urban renewal and the destruction of sections of older cities and whole buildings such asPennsylvania Station (1961) in New York and the construction of unsympathetic modern structures. A reevaluation of the American built past took place with new recognition of the more recent Victorian, American Renaissance, and Art Deco buildings and even streamlined diners. One effect of the preservation movement has been to direct attention to the validity of historically based design. Within inner cities there developed an acknowledgment of the historic townscape and a contextual approach to design. Kevin Roche, a modernist, continued the original architect Francoise Ier’s style for an addition to the Jewish Museum (1989) in New York; in Washington, D.C., for a new building in the Federal Triangle, James I. Freed, of Pei, Cobb, Freed, employed classical orders for the Reagan International Building (1989–98). Older structures were adapted for new purposes, such as The Cannery (San Francisco, 1968) by Joseph Esherick and Quincy Markets (Boston, 1976) by Ben Thompson. These so-called “festival markets” helped influence a semisuccessful attempt to revive main streets across the country. The New Urbanism movement spearheaded by Duany and Plater-Zyberk at Seaside, Florida, and other places and by the firm Cooper-Robertson (Alexander Cooper and Jaquelin Robertson) and others at Celebration, Florida, draws on nostalgic interpretations of the 19th- and early 20th-century small town. All types of revival houses compete for attention. In a sense these are architectural theme parks—Disneyland as permanent lifestyle. The power of historicism and nostalgia for an earlier time are strong traits in America and have created one of its most enduring legacies.

Regionalism and Nativism

The search for a native American architecture that could be based on the local vernacular or nature has animated many architects. A recognition of localized conditions of environment can be traced far back in American history, but regionalism as a coherent architectural approach owes a debt to the Arts and Crafts philosophy of William Morris and his followers that reached America from the 1870s onward. Simple overall form and complex details became a trademark of both furniture and buildings, which often had wood peg joints and leaded glass windows contrasted with plain woodwork. In England one of the fundamental touchstones was an antimachine, anti-industry attitude and a return of artisans to the production of objects and buildings. Some Americans did adopt a handicraft ethic—especially decorative arts artisans—but overall Americans remained tied to the machine, and the Arts and Crafts aesthetic was widely commercialized in America. Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1901 talk, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” noted that the machine could better provide the aesthetic qualities of simplicity and rectilinearity than the hand.

The Arts and Crafts movement in America persisted into the 1920s. Although the overall intention was for a regional response, the movement existed at the national level through the writings of publicists like Gustav Stickley and The Craftsman magazine. Stickley and others popularized the concept of the bungalow, the low-rising story- tostory-and-a-half house that fit easily into the landscape of suburbia and nature. Bungalows appeared from coast to coast and became the archetypal nativist house for the period of 1900 to 1925. In southern California, Irving Gill abstracted the Mission into asimplified concrete type of construction that was remarkable for its absence of details and purity of form. Also in southern California, brothers Charles Sumner and Henry Mather Greene created a very different expression, making the shingle-covered wood bungalow into an exquisite art object of delicately wrought construction. The basis of their design was the local vernacular and the elaboration of wood construction, as in the Gamble house (Pasadena, California, 1906–08). Farther north, in the Bay Area around San Francisco, Bernard Maybeck created his own personalized—and eclectic—regional response, using various foreign and American elements.

The Chicago area, led by Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, created a distinctive regionalism in the Prairie School. Sullivan’s early work was large, urban, and commercial, but after 1900 he found such commissions difficult to secure and turned to house and small-town bank designs that fit squarely within the Arts and Crafts regional ethic. His National Farmer’s Bank (1907), Owatonna, Minnesota, designed in conjunction with George Grant Elmslie, demonstrated a nativistic and original creation of ornament drawn from nature and geometry. Sullivan represented one side of the Prairie School; his descendants William Gray Purcell and Elmslie followed his lead with essentially boxy forms articulated by openings, structural members, and ornament.

Wright, who had worked for Sullivan, represents the other, better-known side of the Prairie style. Wright openly attempted to recall the landscape through low-rising forms, open spaces, and ornamental details. Except for his earliest buildings and his inexpensive housing solutions, Wright tended to break apart the form, to stretch it out, to articulate the parts into a coherent whole. The Robie House (Chicago, 1906–08) is composed of a series of layers that move upward and outward, pinned to the earth by a large chimney core, and that shelter a continuous living-dining space. Out of Wright’s Oak Park Studio came a group of architects such as Walter Burley Griffin, Marion Mahony, and others who elaborated Wright’s ideas and helped spread them not only nationwide but internationally.

Wright’s career in the United States went into an eclipse between 1914 and 1936; he built little except for works in Tokyo and southern California. This work moves beyond the Arts and Crafts, as Wright attempted to create a native language appropriate to the site. In the Los Angeles area, Wright drew on preColumbian Indian forms. Although viewed as a modernist abroad and by many at home, Wright always claimed that his architecture came from American conditions, and he employed the word “organic” as a definition. Fallingwater (Bear Run, Pennsylvania, 1935–37) announced Wright’s return to prominence and posited that American modern design should respond to the localized conditions of site. His later Usonian houses and the Guggenheim Museum (New York City, 1943–59) were attempts to forge an American architecture free of either historical or European modern prototypes.

Later followers of Wright in this quest for a nativist American design would include his Taliesin Fellowship, a few of his students, E.Fay Jones, and at some removal, independents like Bruce Goff.Jones’s work has Wrightian forms and details, though with more vertical articulation. His Interdenominational Chapel (1980), Thorncrown, Arkansas, uses wooden uprights and trusses to create a magical space in the middle of a grove. Goff s work has no parallels, for although he admitted to initially being affected by Wright, his designs departed from the essentially geometrical basis of Wright. Goffeccentrically used prows, peaks, towers, carpeted walls, and fringe. His Ford House (Aurora, Illinois, 1947–50) is a round shape with two attached bedroom pods; the form is composed of lower walls of coal embedded with hunks of green glass that carry a Quonset hut frame covered in lapped siding and shingles. The interior, as with most of Goff s work, is unsettling in its unconventionality and exhilarating in its expansiveness.

Another branch of regionalism, more historically based, continued in the 1920s and 1930s with architects such as John Gaw Meem in New Mexico, Robert McGoodwin in Pennsylvania, and Royal Barry Wills in Massachusetts. They designed buildings that eclectically drew on the local vernacular imagery and met modern requirements. The work of these regionalists was accomplished and in many cases distinguished; Wills’s work was especially influential because he publicized it through a series of books for homeowners, whereas Meem created an image for an entire region.

Beginning in the 1930s, a new school of abstract regionalism developed in the far west, where architects in southern California (Harwell Hamilton Harris), in the Bay Area (William Wurster), and in Oregon (Pietro Belluschi) drew on the local vernacular of cabins, barns, and ranches and also on the earlier work of Maybeck and the brothers Greene. Harris and Wurster created a “woodsy” California vernacular, using the older ranch house plan, but with open plans and simplified details influenced by the International Style. By the late 1940s, a new West Coast School was openly acknowledged, though it sometimes went under more specific names: the Redwood School, or the Bay Area Group. In the 1950s and 1960s came Joseph Esherick and the firm of Moore, Lyndon, Trumbull and Whitaker. The latter’s work at Sea Ranch (1964– 74), with Lawrence Halprin, picked up on the mid-19th century wooden forms from the nearby Russian settlement at Fort Ross and combined them with landscape sensitivity. Also emerging in the late 1960s and 1970s as part of the counterculture revolution would be a “butcher block,” or ad hoc aesthetic of buildings constructed of seemingly random elements for specific sites.

The term “critical regionalism,” coined by the critic Kenneth Frampton in 1983, although seeming to indicate a regionalist response, was really a recognition of certain local modernist idioms that had grown up internationally. Placing stress on tectonics and building processes, critical regionalism was really a critique of Postmodernism. Architects sometimes labeled as critical regionalists—Samuel Mockbee and Clark and Menefee—do draw on the local forms, but in a modernist vein. Antoine Predock created in the southwest a compelling abstraction of landscape and indigenous building forms, as in the Fine Arts Center (1985–89), Arizona State University, Tempe. The large geometric forms exude an air of nativist mystery in the harsh sunlight.

Modernism

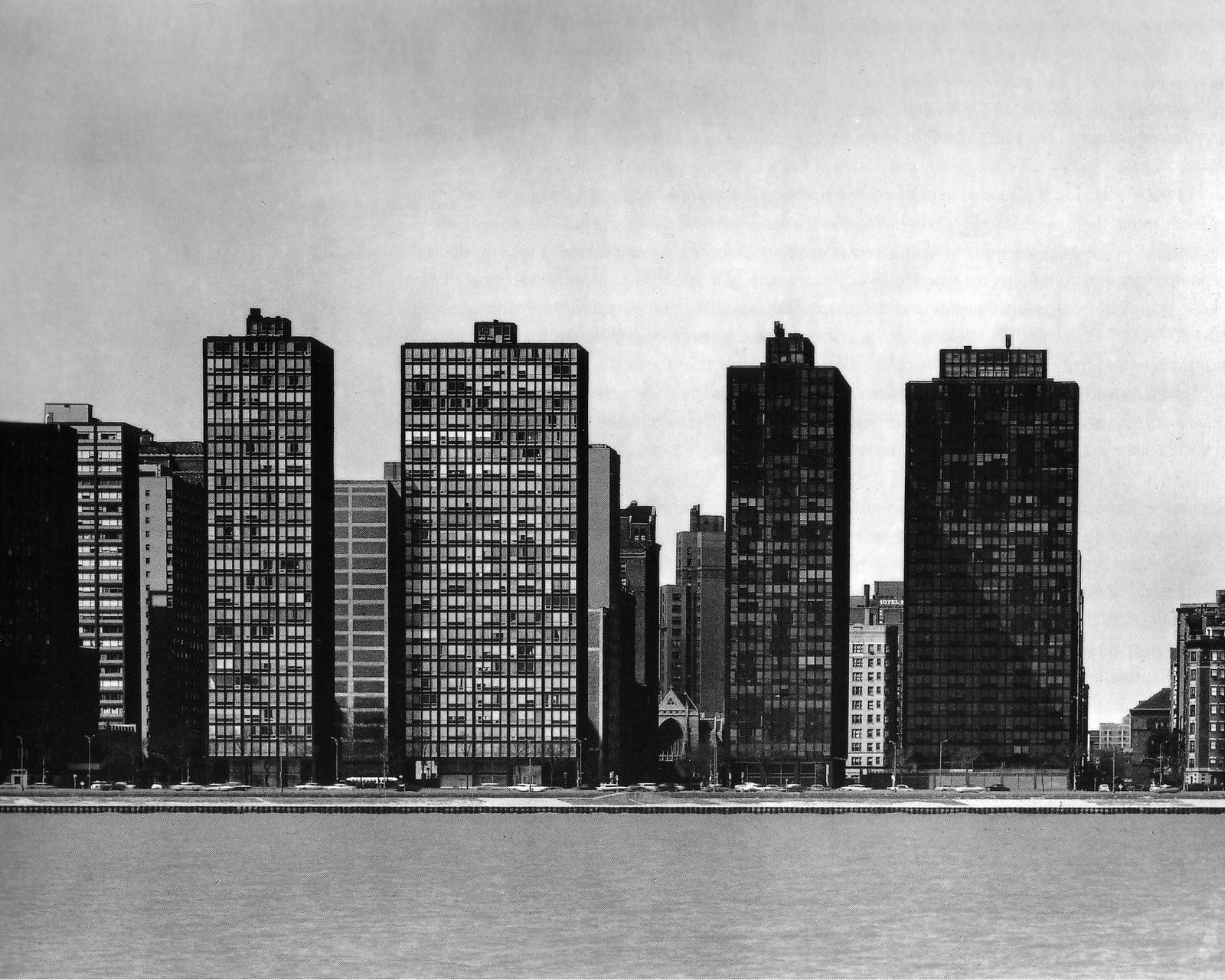

The quest for a new or modern architecture dominated much of 20th-century American architectural thought. A polemical warfare existed between factions who attempted to define modern architecture by rigid stylistic criteria. With historical perspective, however, one can see modernism as a broad theme that contains—and continues to have—a number of different thrusts and styles or idioms, which might be labeleddecorative, constructive, abstract, and Postmodern. Common to all approaches was a belief that reliance on older historical styles was intellectually bankrupt, given the tremendous social and technological changes that had occurred. A zeitgeist, or a new spirit, had arisen, brought into being by the machine or other technological advances. Architects would be avant-garde, and like painters they should create a new expression. All architectural modernists paid at least lip service to the notion of functionalism, but how it was interpreted differed widely. Few architects belonged exclusively to the decorative, constructive, abstract, or Postmodern approach. Mies van der Rohe argued that his buildings were reflective of their structure with their revealed frame, as with the apartment towers on Lake Shore Drive (Chicago, 1948–51). However, Mies was equally concerned with creating elegant abstract objects irrespective of the revealed frame, as in his Seagram Building (New York City, 1954–58). Similarly, Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson noted the new methods of construction as a basis for The International Style (1932), a book they wrote in conjunction with an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. However, they argued that the International Style existed irrespective of technology, with its own abstract principles that included the avoidance of applied decoration, volume rather than mass, and regularity rather than symmetry. The International Style is similar to the American Renaissance in the attempt to fix a single national architecture for all purposes. In this concern for a new universal style, some modernists stand out. Mies van der Rohe created forms that could be—and were—built everywhere.

The decorative modernist approach first emerged in the 1920s and 1930s and frequently goes under the name of Art Deco or Art Moderne. Some American architecture was directly influenced by the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts, Paris (1925), and also by the European Secessionist movement. This comes forth most obviously in the ornamental appliqué Eliel Saarinen placed on his Chicago Tribune Tower entry (1922) or in Parkinson and Parkinson’s Bullocks-Wilshire Department Store (Los Angeles, 1928). Saarinen’s later work remains within the decorative tradition seen especially in his highly colorful Kingswood School (Cranbrook, Michigan, 1929–31). In the later 1930s and 1940s, he evolved a more reticent and simpler modernism, though it was tied to the ornamental texture of materials.

An aspect of the Art Deco was geometrical elements in a setback form with appropriate ornament, which appeared in Bertram Goodhue’s Nebraska State Capitol (Lincoln, 1921–31) and then in skyscrapers by Ralph Walker, Raymond Hood, and William Van Alen. The 1916 New York zoning regulations helped in this development because they mandated setbacks in high-rise buildings, and architects across the country imitated the form, irrespective of local zoning regulations. Hugh Ferris, an architectural renderer, showed architects how the setbacks of the tall masses could be molded. Van Alen’s Chrysler Building (New York City, 1928–31) combined setbacks with a stainless steel radiating crest. At an urban scale, Raymond Hood, as the leader of a team of architects, planned Rockefeller Center (New York City, 1928–38)—a group of extravagantly decorated setback buildings.

A new decorative approach appeared in the 1950s and 1960s in some works by Philip Johnson, Wallace K.Harrison, Minoru Yamasaki, and Edward Durell Stone. They introduced patterned blocks and screens and also created forms that recalled classicism,as in Stone’s United States Embassy (1954) in New Delhi, India. Johnson’s Sheldon Museum (1960–63), University of Nebraska, is bounded by decorative, ahistorical pilasters and arches with subtle curves and profiles that are perhaps too graceful.

The Constructivist approach takes as its premise that technology and construction are the major design determinants and should be reflected in the final product. The 19thcentury Chicago School, with its emphasis on the revealed frame, was a major influence on American architecture from the 1930s onward. Construction as the form determinant can be seen most prominently in the work of Albert Kahn, a leading factory designer in the first half of the 20th century. He produced large, elegant factories of curtain walls enclosing trusses, columns, and open interior spaces. In California the Case Study housing program of the 1940s and 1950s, led by designers such as Charles Eames and Craig Ellwood, created steel-framed houses out of industrial components. A High-Tech sensibility emerged in which great prominence was given to industrial materials, the structure, and the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. The later work of Ellwood (Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California, 1977), the early work of Hardy, Holtzman and Pfeiffer (Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1974), and the work of Helmut Jahn (Michigan City, Indiana, Public Library, 1977) all exploited technology both as the basic expression of the building and as ornament.

Far different is the Brutalist approach of Louis Kahn, who saw technology and structure as elements to emphasize, as with the giant laboratory exhausts and reinforcedconcrete, prestressed, posttensioned framing elements in the Richards Medical Laboratory (Philadelphia, 1957–61). Kahn acted as a father figure to a group of Philadelphia-based architects such as Romaldo Giurgola. Kahn’s work, however, is more than just construction; it is also a concern for light and an employment of abstract references to historical prototypes such as the Italian hill town towers at the Richards Laboratory; the Romanesque barrel vaults at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas; or the tapering Egyptian pylons and Renaissance palazzos at the Phillips Exeter Library (Exeter, New Hampshire, 1965–71). As with many creative architects, Kahn escapes any precise classification.

Abstract modernism, the third major direction, is a radical ahistoricism in which all traditional imagery is absent. It first appeared in the work of émigrés such as R.M.Schindler and Richard Neutra. Schindler wanted an architecture that bore no relation to anything of the past and equally avoided contemporary stylisms. His Lovell Beach House (Newport Beach, California, 1924–26) was a series of stacked trays held aloft by a concrete frame and his later houses were exploded boxes of “Space Architecture,” as he claimed, perched precariously on hillsides. Schindler fits in no stylistic categories, whereas Richard Neutra was more derivative of the Europe-based International Style. His Lovell Health House (Los Angeles, 1927–29), with its white gunite skin and steel frame, was actually more advanced technologically than its European contemporaries.

Technology was always an important element of abstract modernism, but never a determinant. The arrival in the later 1930s of another group of European émigrés such as Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Mies van der Rohe helped to make abstract modernism into the dominant American expression. Mies was the more important formgiver, and through his teaching in the College of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago—his campus design served as a demonstration—his steel-and-glass expression came to dominate American cities.

American followers of the International Style included George Howe, who with the Swiss émigré William Lescaze designed the PSFS Building (Philadelphia, 1929–32). The PSFS skyscraper, with its cool, high-styled abstraction, became a forerunner of a postWorld War II phenomenon—the large, aggressively modern corporate headquarters. Instead of the safety of history as an image to be associated with, corporation presidents now sought the novel and modern. The American firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill became the acknowledged leaders of this building type. Under the guidance of designers Gordon Bunshaft and Bruce Graham, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill created crisp and elegant skyscrapers including the Lever House (New York City, 1949–52) and the Sears Tower (Chicago, 1974–76), as well as suburban headquarters such as Connecticut General Life (Bloomfield, Connecticut, 1954–57). The glass office tower assumed political symbolism with the United Nations Headquarters (New York City, 1947–52), designed by Wallace K.Harrison in association with foreign advisers.

Eero Saarinen provided a challenging pluralism of a different style for each commission in contrast to the single-minded steeland-glass approach. His General Motors Technical Center (Warren, Michigan, 1948–56) suggested a Miesian aesthetic, but he increasingly recognized that form knew no boundaries. In his later works such as the TWA Airport Terminal (1956–62) at New York’s John F.Kennedy Airport, or the Dulles Airport Terminal in Chantilly, Virginia (1958–62), Saarinen created tremendously dynamic forms. He also explored a historical contextualism in Morse and Stiles Colleges, Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut, 1958–62), in which the earlier Gothic Revival campus was loosely recalled.

A roughness of concrete and dramatic sculptural form similar to Le Corbusier’s late manner at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1960–63) became a popular idiom with a group of architects from the late 1950s through the early 1970s. Paul Rudolph’s Yale University Art and Architecture Building (New Haven, Connecticut, 1958–62) echoes both Wright and Le Corbusier in forms. Although Brutalism found a following, more important was the “rebirth of solids” and “a new plasticity,” as Marcel Breuer explained it. He exploited the massive concrete frame in a series of large bureaucratic office buildings in the United States and abroad.

From the 1960s onward, minimalist and scaleless exterior forms reflecting the contemporaneous minimal art movement in painting and sculpture became a line of development in abstract modernism. Gordon Bunshaft’s Hirshhorn Museum (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1967–74) was essentially a large piece of sculpture—a pure round and monolithic form. Exteriors of buildings appeared to become a single, unified material, such as reflective glass on I.M. Pei and Henry Cobb’s John Hancock Buildings (Boston, 1973–77), Kevin Roche’s U.N. Plaza (New York City, 1976–83), or Cesar Pelli’s Pacific Design Center (Los Angeles, 1973–75). The reflective glass skin was an American trademark; similarly, long stretches of limestone with few subdivisions, as in Pei’s East Wing of the National Gallery (Washington, D.C., 1968–78), also produced this clean, minimal effect.

The “white box” of the 1920s International Style experienced a revival in the 1960s and 1970s via a younger generation. The “New York Five” (Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman, John Hedjuk, and Charles Gwathmey) were greatly influencedby Le Corbusier’s pavilions of the 1920s and by the Anglo-American critic Colin Rowe. All moved on to different work, though Meier retained the most allegiance, showing an ability to inflate the white box into a large and more complicated scale, as with his U.S. Courthouse (Central Islip, New York, 2000).

Postmodernism in the 1970s and 1980s might have been considered a separate theme, but as the term implies, it was (or is) not a total break with modernism, but the opening of a discourse with subjects that modernism had ignored up to that point. Born of a sense of disillusionment and what was termed at the time a “failure” of abstract and technological modernism, Postmodernism frequently exhibited a contextual approach in design and a certain nostalgia for the past that contained analogies with decorative modernism. The term Postmodernism did not receive wide currency until its adoption by proponents such as Robert A.M.Stern and Charles Jencks in the mid-1970s, but its roots go back to the dissatisfaction with modernism seen in the work of Johnson, Stone, and others in the 1950s. Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) criticized the modernist fascination with isolated buildings. Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) and his later (with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour) Learning from Las Vegas (1972) were the earliest key texts of the movement. Influenced by the contemporaneous pop art movement, Venturi argued that architects should look to the roadside “strip” and that buildings were primarily “signs” with communicative systems involving nonfunctional elements such as ornament. Symbolism treated with irony became his firm’s trademark. Venturi’s mother’s house (Vanna Venturi House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1962–64) reflects this approach with raised moldings, an oblique entrance, and a split gable that can be read as a pediment. Venturi and his partners frequently demonstrate a witty streak, as in the play on the 1910s revival of the English Jacobean Revival at Princeton University in their Wu Hall (Princeton, New Jersey, 1980–83). Initially, Charles Moore’s architecture of the 1960s had a regionalist orientation, as at Sea Ranch condominiums (Sea Ranch, California, 1964–65); however, Moore also showed a sensibility to history and used ornament in an unorthodox and even distorted manner. A peripatetic teacher at many schools and universities, Moore influenced a tremendous number of younger architects. Stylized references through abstraction and distortion to earlier buildings and forms can be seen as the basis of a group of Postmodernists such as Michael Graves. Graves, who began as a neo-Le Corbusian in his earlier works, retained a modernist search for a distinctive personal language. His Public Services Building (Portland, Oregon, 1980–82), with its unique polychrome pastels and over-scaled and patently false applied classical detail, contains a lurking figurative molding of space and form. Similarly, his Den-ver Public Library (1995) has a relation to the particularized western mining context but contains its own individuality. Postmodernism’s critique of the failure of modernism included its lack of theory that went beyond function and technology. The result was a theory fad that crashed through academia and promoted approaches drawn from other disciplines such as semiotics, anthropology, and gender studies. The most prominent was a form of abstract modernism called deconstructivism, which emerged in the 1980s and drew on French literary theory and philosophy and also on the Russian Constructivism of the 1920s. Deconstructivist architecture existed not as a unified approach but as a group of individuals, including Peter Eisenman, who challenged harmony, unity, and stability bydesigning buildings or theoretical projects in which forms are rotated, along with the appearance of odd angles, disruptive materials, and a general sense of alienation of the occupant. As shown in his Wexner Center (1985–89), Ohio State University, and the Columbus Convention Center (1989–92)—both in Columbus, Ohio—Eisenman’s work is characterized by a progressive distortion and an additive and subtractive design process to create conflict-ridden, unsettling forms.

Avoiding this complex theoretical base, a new wave of abstract modernism far more sculptural and distorted in form emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, as seen in the work of Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne and Morphosis, and Eric Owen Moss—all centered in the Los Angeles area. Gehry’s early work, such as his own house (Santa Monica, California, 1977–78, 1992), delighted in collage and the treatment of fragmentary elements in unorthodox ways, including asphalt floors, open stud frames, and chainlink fencing. As Gehry’s work developed, it became more sculptural, as with his Advanced Technology Laboratory (1987–92) at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and the Guggenheim Museum (Bilbao, Spain, 1993–97). The Iowa work is composed of tiled geometrical blocks, whereas in Spain, the 258,000-square-foot museum exudes a strongly organic feel with its long curling surfaces. Partially clad in titanium, the Bilbao structure continues the collage approach with its juncture of various geometries and materials.

Gehry’s Guggenheim at Bilbao and other late 20th-century works such as the Korean Presbyterian Church (2000), Queens, New York, by Garofalo, with Lynn and McInturf— with its extruded frame like wings—have been likened to computer-created designs. Certainly, the working drawings and building materials fabrication were done by computer programs. Computers did aid in opening Gehry and Garofalo’s vision to new exciting and abstract forms, but computers did not create the fantastic forms that were still products of the designers’ imaginations.

At the end of the 20th century, American architecture was as diffuse as Gehry’s project for a 40-story-tall new Guggenheim building in New York and Robert A.M.Stern’s design for a Public Library in Nashville, Tennessee. Gehry’s project is a wild combination of forms, whereas Stern’s library recalls Paul Cret’s work of the 1930s. They represent an alpha and omega of architecture: two extremely different ideas of what is American. This multiplicity of approaches in American architecture during the 20th century is its ultimate characteristic. The consequence has been many competing themes and approaches with none totally dominant and, indeed, no promise of that occurrence in the near future.

RICHARD GUY WILSON

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.3. Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1901, Frank Thomas House, Oak Park, Illinois, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1909, Robie House, South Woodlawn, Chicago, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1936-1937, Fallingwater House, PENNSYLVANIA, UNITED STATES, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1936-1939, Johnson Wax Building, RACINE, WISCONSIN, UNITED STATES, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949, The Glass House, USA, PHILIP JOHNSON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949, CASE STUDY HOUSE 8: THE EAMES HOUSE , USA, CHARLES AND RAY EAMES |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949-1950, United Nations Headquarters, New York, USA, GROUP OF ARCHITECTS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1951, Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1951, 860-880 Lake Shore Apartments, Chicago, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1953-1968, St. John's Abbey and University, Collegeville, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1956, S.R. Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1956-1962, United States Air Force Academy,

Colorado Springs, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1958, The Seagram Building, New York, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1959, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

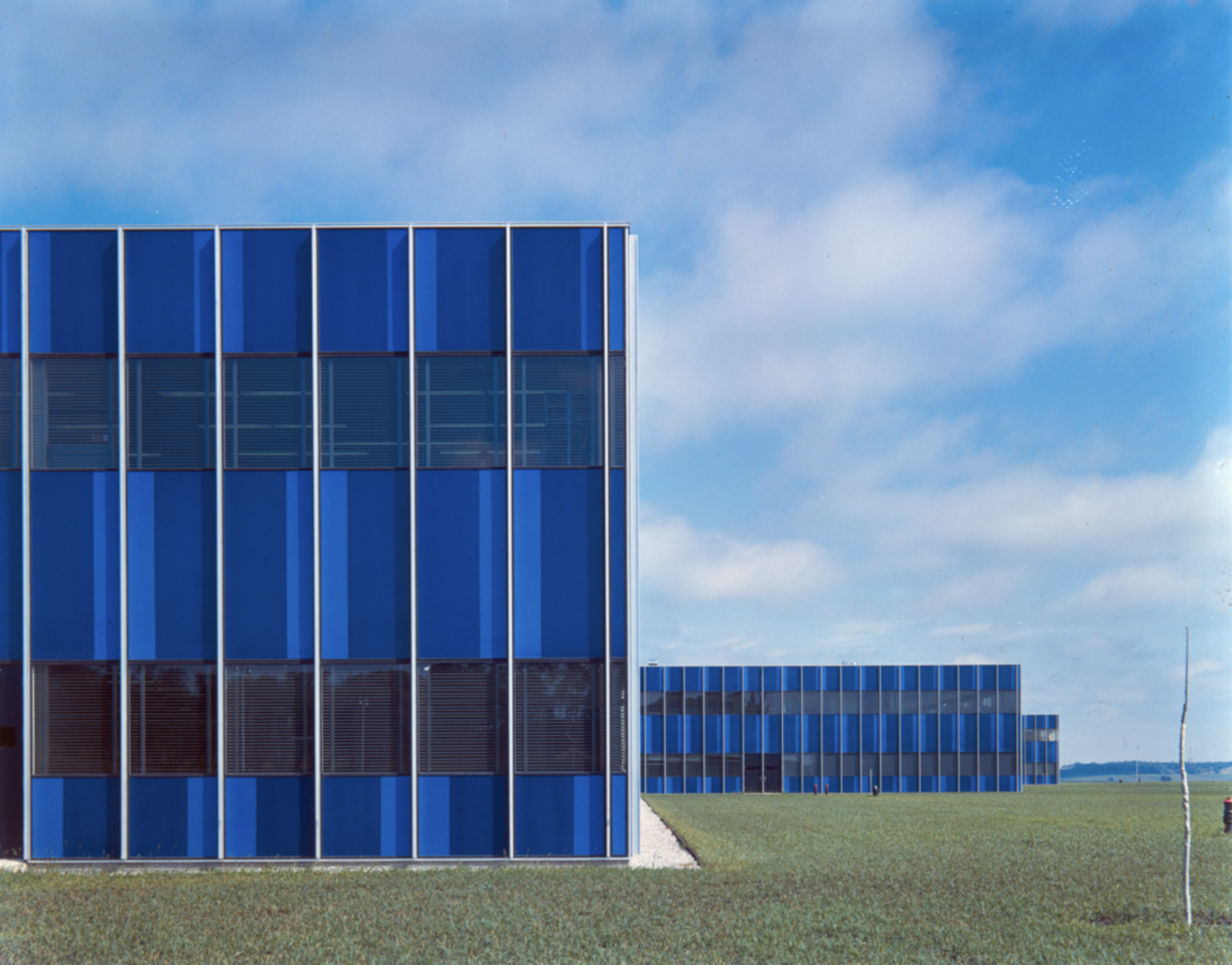

1959, IBM Manufacturing Plan, Rochester, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1959-1967, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1962, Dulles International Airport, Chantilly, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

, New York, USA, EERO SAARINEN.png) |

| |

1964, Columbia Broadcasting System Headquarters (CBS Building), New York, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1965-1971, Library and Dining Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

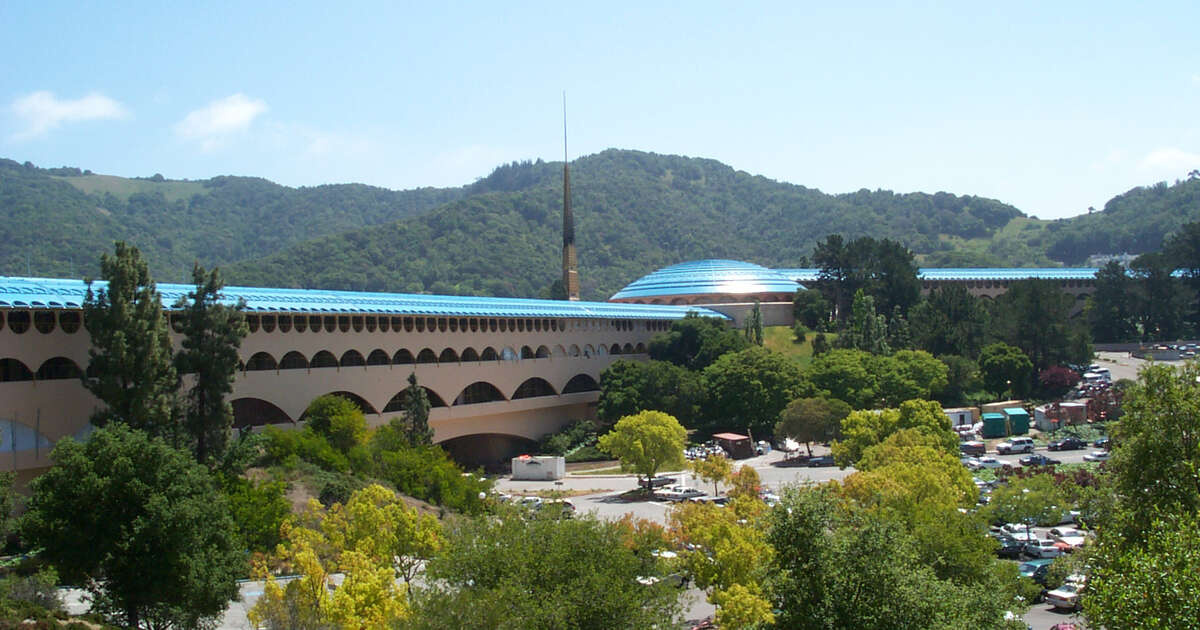

1966, Marin County Civic Center, San Raphael, California, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1966-1972, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1968, St. Louis Arch, St. Louis, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1968, Alcoa Building, San Francisco, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1970, John Hancock Center, Chicago, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1970-1974, Sears Tower, Chicago, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1975-1979, The Atheneum, New Harmony, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978, National Gallery of Art, East Building, Washington, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978-1982, JPMorgan Chase Tower, Houston, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1997, The Getty Center, Los Angeles, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-1995, MOMA museum of modern art, San Francisco, USA, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, De Young Museum, San Francisco, USA, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2017, Steve Jobs Theater, Cupertino, USA, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

ARCHITECTS: UNITED STATES

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1901, Frank Thomas House, Oak Park, Illinois, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1909, Robie House, South Woodlawn, Chicago, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1922, Schindler House, West Hollywood, USA, RUDOLPH M. SCHINDLER |

| |

|

| |

1927-1929, Lovell House, Los Angeles, USA, RICHARD NEUTRA |

| |

|

| |

1936-1937, Fallingwater House, PENNSYLVANIA, UNITED STATES, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1936-1939, Johnson Wax Building, RACINE, WISCONSIN, UNITED STATES, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1949, The Glass House, USA, PHILIP JOHNSON |

| |

|

| |

1949, CASE STUDY HOUSE 8: THE EAMES HOUSE , USA, CHARLES AND RAY EAMES |

| |

|

| |

1949-1950, United Nations Headquarters, New York, USA, GROUP OF ARCHITECTS |

| |

|

| |

1951, Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1951, 860-880 Lake Shore Apartments, Chicago, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1953-1968, St. John's Abbey and University,

Collegeville, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

1956, S.R. Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1956, General Motors Technical Center,

Warren, USA |

| |

|

| |

1956-1962, United States Air Force Academy,

Colorado Springs, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1956-1958, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Cullinan Hall), Houston, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1957, Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1958, The Seagram Building, New York, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1959, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1959, IBM Manufacturing Plan, Rochester, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1959-1967, Salk Institute for Biological Studies,

San Diego, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1962, TWA Terminal, New York, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1962, Samuel F.B.Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges,

Yale University, New Haven, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1962, Dulles International Airport,

Chantilly, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1964, Columbia Broadcasting System Headquarters

(CBS Building), New York, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1964-1966, Whitney Museum of American Art,

New York, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

1965-1971, Library and Dining Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy,

Exeter, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1966, Marin County Civic Center, San Raphael, California, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1966-1972, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1968, St. Louis Arch, St. Louis, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1968, Alcoa Building, San Francisco, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1970, John Hancock Center, Chicago, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1970-1974, Sears Tower, Chicago, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1971, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, USA, BREUER, MARCEL |

| |

|

| |

1973-1978, 23 Beekman Place, New York, USA, PAUL RUDOLPH |

| |

|

| |

1975-1979, The Atheneum, New Harmony, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1978, National Gallery of Art, East Building,

Washington, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1978-1982, JPMorgan Chase Tower, Houston, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1980-1983, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1984-1997, The Getty Center, Los Angeles, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1989-1995, MOMA museum of modern art, San Francisco, USA, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

2000-2009, CHICAGO ART INSTITUTE – THE MODERN WING, CHICAGO, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, De Young Museum,

San Francisco, USA, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2017, Steve Jobs Theater, Cupertino, USA, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

ART DECO; ART NOUVEAU; ARTS AND CRAFTS; BREUER, MARCEL; BRUTALISM; CLASSICISM; DECONSTRUCTIVISM; EISENMAN, PETER D.; ELLWOOD, CRAIG; GEHRY, FRANK OWEN; INTERNATIONAL STYLE; KAHN, ALBERT; KAHN, LOUIS I.; NEUTRA, RICHARD; POSTMODERNISM; SAARINEN, EERO; SCHINDLER, RUDOLPH M.; VENTURI, ROBERT; WRIGHT, FRANK LLOYD;

FURTHER READING

Brooks, H.Allen, The Prairie School; Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwest Contemporaries, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972

Condit, Carl, Chicago, 1930–70: Building, Planning, and Urban Technology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974

Ferriss, Hugh, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, New York: I.Washburn, 1929

Frampton, Kenneth, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, New York: Oxford University Press, 1980

Frampton, Kenneth, and John Cava (editors), Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995

Handlin, David P., American Architecture, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985 Hitchcock, Henry-Russell, Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, third edition, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell, and Philip Johnson, The International Style: Architecture since 1922, New York: The Museum of Modern Art and W.W.Norton, 1932

Jacobs, Jane, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Random House, 1961

Jencks, Charles A., The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, New York: Rizzoli, 1977

Johnson, Philip, and Mark Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988

Jordy, William, American Buildings and Their Architects: Progressive and Academic Ideals at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, volume 3, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1972

Jordy, William, American Buildings and Their Architects: The Impact of European Modernism in the Mid-Twentieth Century, volume 4, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1972

Kimball, Fiske, American Architecture, Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill, 1928

Mumford, Lewis, Sticks and Stones: A Study of American Architecture and Civilization, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925

Roth, Leland, American Architecture: A History, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2001

Roth, Leland (editor), America Builds: Source Documents in American Architecture and Planning, New York: Harper and Row, 1983

Rowe, Colin, and Fred Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1977

Scully, Vincent, American Architecture and Urbanism, revised edition, New York: H.Holt, 1988

Stern, Robert A.M. New Directions in American Architecture, New York: G.Braziller, 1977

Tallmadge, Thomas E., The Story of Architecture in America, revised edition, New York: W.W.Norton, 1936

Upton, Dell, Architecture in the United States, New York: Oxford University Press, 1998

Venturi, Robert, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, New York: Museum of Modern Art, and Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1966

Venturi, Robert, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1972

Wilson, Richard Guy, The AIA Gold Medal, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984

Wilson, Richard Guy, Dianne Pilgrim, and Dickran Tashijan, The Machine Age in America, 1918–1941, New York: Abrams, 1986

Wilson, Richard Guy, and Sidney K.Robinson (editors), Modern Architecture in America: Visions and Revisions, Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1991

Wright, Frank Lloyd, When Democracy Builds, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945

Wright, Frank Lloyd, An Organic Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy, the Sir George Watson lectures of the Sulgrave Manor Board for 1939, London: Lund Humphries, 1970

Zukowsky, John (editor), Chicago Architecture, 1872–1922: Birth of a Metropolis, Munich: Prestel-Verlag and Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1987

Zukowsky, John (editor), Chicago Architecture and Design, 1923–1993: Reconfiguration of an American Metropolis, Munich: Prestel-Verlag and Ernest R.Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago and New York: Neues Publishing, 1993

American masterworks the twentieth-century house

American building art the nineteenth century

American architecture now II

American architecture and urbanism

Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States: The Suburbanization of the United States

California Design, 1930--1965: ''Living in a Modern Way''

Built in USA: Post-war Architecture

American Buildings and Their Architects: The Impact of European Modernism in the Mid-Twentieth Century: 004

Exiled in America: Life on the Margins in a Residential Motel

The Motel in America (The Road and American Culture)

The Los Angeles House: Decoration and Design in America's 20Th-Century City

To Every Thing a Season: Shibe Park and Urban Philadelphia, 1909-1976

The Architects and the City: Holabird & Roche of Chicago, 1880-1918 (Chicago Architecture and Urbanism)

The Second Generation

The Rise of an American Architecture

American Buildings and Their Architects: The Impact of European Modernism in the Mid-Twentieth Century: 004

American Architecture and Other Writings: Volume I American Architecture and Other Writings, Volume I

American Architecture and Other Writings: Volume II American Architecture and Other Writings, Volume II

Architecture in North America Since 1960

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

New Directions in American Architecture

Guide to U.S. architecture, 1940-1980 |

| |

|

|